My previous column posed a question: if European Union policymakers can’t take big strides towards capital markets union now, when will they? Europe has no alternative but to assertively push ahead, under the urgent cover of geopolitical crisis, to implement the reforms it’s failed to carry out in over 10 years to harmonize its capital markets. In the world we currently inhabit, kicking the can down the road won’t cut it.

Nowhere is Europe’s lack of response more visible than in its continued dependence on the US dollar, which puts its governments, companies and banks at the mercy of a testy White House actively working to politicize the Federal Reserve. In previous times, having the Fed reduce or suspend, let alone cancel, discretionary liquidity facilities such as US dollar swap lines – or even threaten to do so – was unthinkable. Not least because of the impact on global financial stability and adverse blowback to US financial markets.

It would still shock today, but in the more politicised air pocket the Fed has been forced into, it would shock a great deal less. The US administration has not made overt threats about the US dollar backstop yet, but it is a topic that is swirling around the ether because US appears more than prepared to use political leverage whenever, wherever and however it sees fit.

Lower dollar borrowing not sign of strength

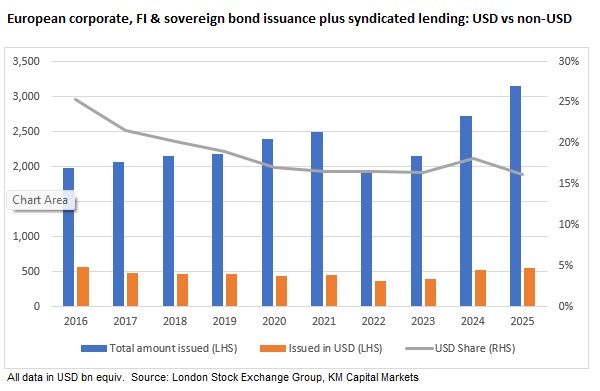

Given the environment we’re in, I was curious to gauge the extent of US dollar borrowing by European sovereigns, banks and corporates in the syndicated loan and public bond markets. It’s an important part of the overall picture, accounting for over US$3.15 trillion equivalent of new funding in 2025 and US$23.2 trillion over the last decade, according to London Stock Exchange Group data.

I was surprised to see that US dollar borrowing by European issuers fell proportionally to its lowest in a decade in 2025 – to just 16% of the total. That’s a dramatic fall from 25% in 2016, and it’s not the result of a precipitous decline in any one year, but a constant downward trajectory:

Counter-intuitive

The reduction in dollar funding over that period has in some ways been counter-intuitive given that the EUR/USD swap basis, a strong relative price signal, has been negative for much of the past decade, technically giving euro-based issuers access to synthetic swap-based euro funding at tighter all-in levels than they could have achieved by issuing in euros.

A variety of idiosyncratic factors in play – issuers’ funding needs, absolute yields and coupon levels, credit conditions, investor behaviour, macroeconomic conditions, monetary accommodation – meant issuers couldn’t always find compellingly executable opportunities so had the latitude to turn down the basis incentive.

But here’s the thing: much of that latitude was created by the artificial cover of unrelated European government and central bank financing and asset purchase programmes and actions that created structurally cheap euro funding just as dollar investors became more selective around European credits when global markets were unsettled.

In other words, the decline in US dollar borrowing reflects temporary distortions in euro funding markets, not a structural shift toward euro‑area financial autonomy. But what an opportunity it was to put policy actions around capital markets union to work to sustain the relative progress.

Strategic vulnerability to weaponized finance

Back to the proportional reduction in US dollar funding by European issuers, can we infer that we’ve reached a pivotal moment that strengthens the hand of Europe’s policymakers and lawmakers in their quest to achieve financial sovereignty at a time of strained relations with an increasingly hostile and capricious US administration? In a word, no. Because the decline in US dollar funding by European issuers was not the result of any co-ordinated strategic policy-driven impetus to make funding at home compelling for issuers.

European funding will continue to be determined by technical and fundamental market and idiosyncratic issuer-related factors. From a microeconomic standpoint, the job of funding officials and treasurers is to hit all-in target funding levels and ensure access to a stable, diversified investor base, not solve systemic vulnerabilities.

Europe’s capital markets union has failed to progress beyond an increasingly worn-out policy slogan. Until Europe’s leaders confront the obstacles and blockages head-on ( tax and insolvency law harmonisation, centralized decision-making, fewer restrictions on cross-border capital flows ), they can continue their performative posturing around financial sovereignty as long as they want while letting Washington wield dollar liquidity as a geopolitical bargaining chip where dollar weaponization is a real risk.

The primary intended outcome of capital markets union in Europe is to create an environment where European corporates and small and medium-sized enterprises can access attractive home-grown funding at the same time as European institutional investors and retail savers gain access to compelling investment and savings opportunities, securing Europe’s regional financial autonomy into the bargain.

Of course, it’s very likely that a subsidiary outcome of broader and deeper euro capital markets would see US institutional investors increase asset allocation to that deeper market, enhancing the funding advantages of European issuers and in the process attracting more US debt issuers, which could achieve keener funding costs by issuing in euros to create swap-based dollar funding. That would be an ironic outcome but would also drive home the point that European sovereignty doesn't mean isolationism, it means inter-dependence on Europe’s terms.

How many warnings does it take to change a light bulb?

It’s not as if there haven’t been stark warnings in years past that should have jolted Europe into action:

Those episodes weren’t just funding predicaments; they were geopolitical shocks. Yet Europe has consistently failed to act decisively to get out of the line of fire. Until Europe stops posturing and takes action, its financial institutions and companies will remain vulnerable and powerless price takers in a dollar‑centric world. The solutions are political and structural, not cosmetic, opportunistic or technical.